Melin Llynnon Mill

Logo of Llansadwrn (Anglesey) Weather Station

|

Melin Llynnon MillLogo of Llansadwrn (Anglesey) Weather Station |

|

Melin Llynnon Llynnon Mill is the only working windmill in Wales. It is near Llanddeusant a village in northwest Anglesey (Ynys Môn). It is the only example of what was a common feature of the landscape in the past, as once, there were over 30 working mills on the island. As watermills melinau ddwr had replaced the handmills querns melinau law, of the Middle Ages, so windmills became the preferred method of grinding corn in later years. For all methods of milling Anglesey had a plentiful supply of stone, suitable for millstones, from several quarries. So important, and valuable, were millstones that most quarrying was under royal control. Anglesey millstones maen melin Ynys Môn were greatly sort after, the best stones came from the limestone quarries at Mathafarn Eithaf, Mathafarn Wion and Penmon run by the Priory1. But watermills required a good supply of water and, while the island is not exactly a dry place, in dry years supplies were inadequate. The streams and rivers  of Anglesey, supported by mill-ponds and dams were not enough. The island, however, is very windy and, when the technology was available, wind-power was the ideal solution. Earliest records for the introduction of wind-power come from a Newborough Bailiff's Accounts, in 1303, where details of the cost of erecting a wooden post mill can be found. This mill cost £18.03.00½ to build and was completed on 28th June 1305. The names of the millers are also known; they were John, Henry and Phillip. The millstones came from the Mathafarn quarry that also supplied, in 1314, millstones worth £1.08.09 to the royal mills in Dublin. In 1327 Einon ab Ieuan of Beaumaris built a windmill on Mill Hill1. A survey2 in 1929 listed over 30 windmills, but there were few still in working order. In 1934 only one mill, the Stanley Mill at Treaddur Bay was still working. This was the last mill of this period to work in Wales and the West of England.

of Anglesey, supported by mill-ponds and dams were not enough. The island, however, is very windy and, when the technology was available, wind-power was the ideal solution. Earliest records for the introduction of wind-power come from a Newborough Bailiff's Accounts, in 1303, where details of the cost of erecting a wooden post mill can be found. This mill cost £18.03.00½ to build and was completed on 28th June 1305. The names of the millers are also known; they were John, Henry and Phillip. The millstones came from the Mathafarn quarry that also supplied, in 1314, millstones worth £1.08.09 to the royal mills in Dublin. In 1327 Einon ab Ieuan of Beaumaris built a windmill on Mill Hill1. A survey2 in 1929 listed over 30 windmills, but there were few still in working order. In 1934 only one mill, the Stanley Mill at Treaddur Bay was still working. This was the last mill of this period to work in Wales and the West of England.

'Andrew Wmn's proposals for erectg a Windmill for £240.13.06 (exclusive of the tower and millstones)'Chas Parry's lre dated 22 March 1776 with Two Bills the one amountg to 14.07.00½ for Hoops Bolt etc delivered in Augt. Sept and Nov. 1775 and the other for Sets of Stone Irons delivered 26 Feb 1776 amounting to 10.04.06'

'John Culshaw's Acct of No. of Days Work at Llynnon Mill beginning 27 Augt. 1775 viz 190 Days at 2s being 19.16.0. — at 2/6 being 6.5.0 in all 26.16.00. in which paper there is an Acct of Money pd to Culshaw by Mr. Jones with a Rect dated 15 March 1776 for 7£ being the paymt of Mr. Jones from A. Wms being his Wages for Work done on Llynnon Mill and another dated 7 May for 8£ in full of all Demands for Work done at Mr. Jones's Mill.'

'Mr. Wrights Lre dated 15 Sept. 1776 with Bill for dressing Cloaths and Canvass etc amountg to 10.01.00'

'Andw Wms's Bill for Timber of £229.15.04½'

'Culshaw's Estimate of the Expense of building Llynnon Mill (exclusive of the Tower) £292.00.00'

The total cost of the building worked out at £529.11.00a

The name of the first miller was Thomas Jones 1756-1846

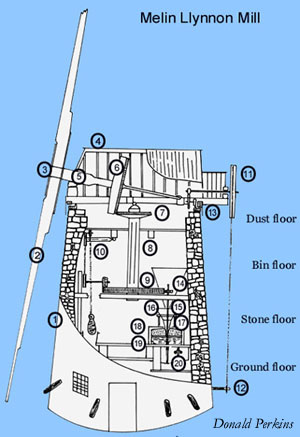

The tower, made of stone, was 30ft 6in (9.3m) tall. It was wider at the base being 19ft 6in (6m) inside diameter and tapered to the top which was covered by a boat shaped cap of 17ft (5.2m) diameter. The mill contains four floors. Starting at the top of the mill the third floor, beneath the cap, is called the dust floor llawr llwch. This serves only to protect the lower floors from dust or rain that could enter the mill from the top and access to machinery. The second floor, the bin floor y yist flawd, is where the grain is stored ready for milling. The first floor, the stone floor llawr carreg, houses the millstones maen melin that grind the flour. The ground floor llawr isaf, receives the ground flour after passing through the stones.

|

Key1. Stone tower2. Sail 3. Iron cross 4. Cap 5. Windshaft 6. Brake wheel 7. Wallower 8. Upright shaft 9. Great spur wheel 10. Sack hoist 11. Chain wheel 12. Wooden cleat 13. Turning gear 14. Stone nut 15. Quant 16. Grain hopper 17. Shoe 18. Runner-stone 19. Bedstone 20. Governor |

To do work the sails must face into the wind. This was one of the miller's tasks and was achieved at ground level by pulling on an endless chain. The chain ran up to a large chain wheel olwyn chaen i droi'r felin i'r gwynt at the top of the tower. The chain wheel 8ft (2.4m) in diameter was connected via gearing to a wooden rack camogau coed resting on the top of the tower. When the chain is pulled the wheel revolves and the cap rotates to the required position.

Through the cap cwch on the top of the mill was fixed a cast-iron windshaft siafft wynt to which a heavy cast-iron cross croes haiarn was attached. The cross carried the latticed sail arms of the windmill that spanned 69ft 6in (21m). These were not flat but had a twist, called the weather trô, similar to an aircraft's propeller blade developed much later. The sails hwyliau varied in width from 7ft 9in (2.4m) at the centre to 6ft 3in (1.9m) at the outside, a characteristic of windmills at the time in Wales and northwest England. On to the lattice arms was spread the sail cloths.

Attached to the cast-iron windshaft is a cogged wooden brake wheel olwyn frec of 8ft 9in (2.7m) diameter that rotates inside the cap. It is called a brake wheel because it has an iron brake on the rim to stop and hold the position of the sails at rest. This wheel turns the the cast iron wallower ymdrybaeddwr and attached to an upright shaft siafft unionsyth of oak wood. This shaft passes down the centre of the mill to the bin floor where it drives the great spur wheel olwyn gocos fawr also made of iron. In turn this drives vertical shafts that turn the millstones (see below) on the stone floor and operates the sack hoist hos sachau. The wheels always work metal against wood. The wooden cogs are usually made of apple wood, that are self lubricating that break from time to time and have to be replaced.

The sack hoist is power driven to lift sacks of grain from the ground floor, through trap doors, to the first floor for milling. The drive is taken from a horizontal shaft off the great spur wheel and power is available whenever the mill is running. An endless chain passes over pulleys that normally run slack. When power is required to hoist a sack the chain is tightened, by pulling on a cord, to take up the drive.

There were 3 pairs of millstones on the first, or stone floor. One pair of French burr stones 4ft (1.2m) diameter was used for wheat and 2 others of local stone 5ft (1.5m) diameter. One of these was used for oats and the other for general grinding purposes. The stones are driven from above by the great spur wheel that turns on a stone nut nyten garreg mounted on top of an iron spindle called a quant polyn. The lower bed-stone is fixed, it is the upper runner-stone that rotates and its speed is controlled, or tentered, by a centrifugal governor rheolwyr. The control process called tentering gwastadau or levelling that sets the distance between the bed-stone and the runner-stone. With more wind the speed of rotation of the mill increases and the stones can be set further apart; more grain can flow between the stones and more flour is produced. Grain, from the sacks on the second floor, is put into a large hopper hopran then to a shoe or small hopper hopran fach shaped like a trough. As the square sectioned quant rotates it shakes the shoe and grain flows into the eye llygad of the runner-stone. The grain is ground between the millstones as it moves from the centre to the outside along grooves cut in the stone. Maintaining the grooves and surface texture of the millstones was an important job. This was done by itinerant stone-dressers who would visit the mill from time to time to dress the millstones.

As the grain is ground the wholemeal flour, emerging from the edges of the millstones, is caught and sent down a shoot to the ground floor. Here is is put into sacks or today into bags for sale. In the past many different types of grain would have been ground at the mill. The main crop would have been oats ceirch as it grows well in the climate of Anglesey and the west of Wales. As the husk is indigestible it must be separated from the digestible seed called a groat grôt. The oats were first roasted in a kiln odyn in a nearby building then passed through a pair of Welsh millstones. Tentering was done manually as it was necessary to set the stones apart the length of an average oat. The husks were split off without damaging the groats and separated in a groat machine. Revolving brushes first brushed out a red coloured dust from roasted hairs on the husk. As the cleaned groats and husks emerged they met air from a 4 bladed wooden fan that blew the lighter husks into a husk cupboard allowing the heavier groats to fall away and be collected. The groat machine was driven from the horizontal shaft that drives the sack hoist. A belt passed over the shaft and passed down through the floor to another in the ceiling of the ground floor.

In 1918 the mill was in full working order until, during a severe storm, the mill was badly damaged. It continued to work on and off for the next 6 years but, as the rotating mechanism was damaged, only when the wind was from the south-west. After that it was left neglected for many years. I remember passing by it, in the early 1960's, when I first came to live on the island. At that time the roof had gone but the sail arms were still mounted on the mill. It was fast deteriorating. But in 1978, the then Ynys Môn (Anglesey) Borough Council purchased the mill and the task of restoration (costing £120,000) was begun3. The mill was reopened in 1986 as a fully working mill. It now produces stoneground flour for sale at the mill.

Melin Llynnon is open to visitors (currently April-September, Tuesday and Bank Holiday Mondays (1100-1700) to Sunday (1300-1700). It is well worth going along for a guided tour and perhaps see the mill working. You can also purchase the stoneground flour produced at the mill.

There is plenty of wind around Anglesey and this natural resource is still being used. There are now 3 wind-farms on the island that are producing electricity for the National Grid. Wind will not runout and it does not cause pollution so there has been much interest in the last decade in generating electricity by wind-power. Within a short distance of Melin Llynnon is National Wind Power's (NWP) Llyn Alaw wind-farm with 34 turbines. The project was completed in 1997 and has a power output of 20.4MW. The farm is at an altitude of about 70m and the height of a tower to the hub is 31m. Each rotar of 44m diameter has 3 blades and rotates at a speed of 30rpm. This produces on average 60,000,000 killowatt hours of electricity every year sufficient to meet the needs of about 14,000 homes. NWP says that the Llyn Alaw turbines prevent about 50,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide and 900 tonnes of acid rain from entering the atmosphere annually. In total the 3 wind-farms of Anglesey can supply 70% of the island's domestic consumption of electricity. Last year in Europe the amount of energy generated by wind-turbines rose by 30%. The European Wind Energy Association says that wind capacity in 2000 exceeded 8900 megawatts. The increases are due to expansion in Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. The Government has set a target of 10% of Britain's energy to be supplied by wind-power by 2010. Wind-power is on-target to provide 100,000 megawatts, that's about 10% of Europe's electricity demand by the year 20204.

In February 2007 the UK wind-power industry had doubled its capacity in under 2 years. With the latest wind farm generating electricity at Braes O'Doune near Stirling, Scotland, adding 72 MW to the National Grid. This brought the UK's wind generation capability up to 2016 MW enough to supply over one million households. But, the UK stands only 7th on the world list of wind generating capacity. Germany with 20,600 MW heads the list with Spain in second place with 11,600 MW and the US with 11,300 in third place. There is still a lot more capacity required, so expect to see more wind turbines appearing in the near future.

1 CARR, Anthony D. 1982. Medieval Anglesey. Publ: Anglesey Antiquarian Society, Llangefni pp373.

2 Anon., 1937. An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Anglesey. The Royal Commission on Ancient & Historical Monuments in Wales & Monmouthshire. Third impression 1968. Publ: HMSO.

3 RAMAGE, Helen. 1987. Portraits of an Island Eighteenth Century Anglesey. Publ: Anglesey Antiquarian Society, Llangefni pp351.

4 NEW SCIENTIST 2000. No. 2224 dated 5 February p23.

aOld currency system: (£.ss.dd) Pounds £ were the same unit, there were 20 shillings to the pound and 12 pence to the shilling or 240 pence to the pound. There were also half-pennies (½) and farthings (¼).

These pages are designed and written by Donald Perkins © 1998 - 2010 Page dated 4 August 2000: |